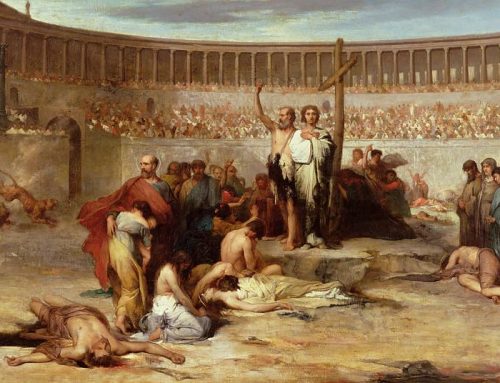

It was a cold night in the camp of Sebaste. Forty young people in their twenties, belonging to the Twelfth Legion, well-known as the Fulminata, waited impatiently for the news. After having been faithful to their beliefs and not having given in to apostasy like so many others, they were persecuted by the Roman Emperor Licinius. In spite of this, these forty soldiers affirmed that no torment would separate them from their religion.

Forty martyrs of sebaste

It was a cold night in the camp of Sebaste. Forty young people in their twenties, belonging to the Twelfth Legion, well-known as the Fulminata, waited impatiently for the news. After having been faithful to their beliefs and not having given in to apostasy like so many others, they were persecuted by the Roman Emperor Licinius. In spite of this, these forty soldiers affirmed that no torment would separate them from their religion.

They were enlisted in a legion of border guards. It seems certain that it was the XIIth legion Fulminata which had taken part in the assault and capture of Jerusalem in the year 70, and then was stationed in the Orient with its headquarters at Melitene in Armenia minor.

There was a kind of Christian tradition within the legion since they had counted Christians in their ranks since the IIIrd century and perhaps even before. Other links with Christians through friendship and marriage developed during their stay in Armenia, where Christians were numerous. The martyrdom took place a little north of Melitene, in a city called Sebastia(Sebaste to be more precise), where perhaps the legion maintained a strong detachment.

The Forty were quite young, in their twenties. Their “testament” says that when they bid farewell to their dear ones, only one had wife and a little child, one had a fiancé, while others saluted their living parents. In general, then, they were in the prime of early manhood.

When the order of Licinius reached the encampment that soldiers must participate in the sacrifice to idols, they refused without hesitation. Arrested forthwith, they were bound with a single chain long enough for all of them and locked up in gaol.

They spent a long time in prison, probably because they were waiting for orders from a higher officer or even- given the gravity of the case – from Licinius himself. During this time of waiting, the prisoners fortelling their end,wrote their collective “testament” by the hand of a certainMeletius, one of their number.

In this important, profoundly Christian document, those about to dieexhorted their relatives and friends to forsake the fleeting goods of this world for the things of the one beyond. They greeted those most dear to them.

The document carries, as usual, the names of all forty martyrs, and thesenames were copied into other texts with small divergences in spelling.

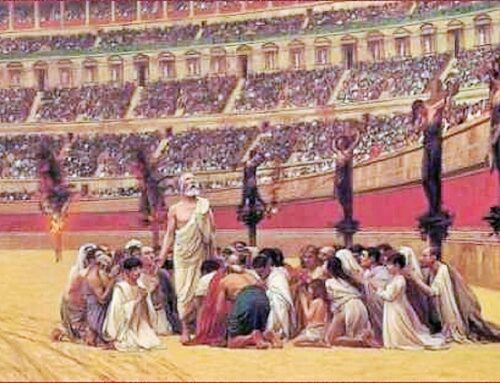

According to the sentence handed down, the forty were to die by exposure: they were put naked at night, in the dead of winter on a frozen lake, and there awaited their end.

The place chosen for the sentence seems to have been a wide courtyard in front of the Baths of Sebastia, where the condemned would be withdrawn from the curiosity and sympathy of the public and at the same time under the supervision of the baths attendants.

In the courtyard was a large water tank, a kind of lake, which was joined to the baths. Basil tells us that the place was in the middle of the city, and beside a lake. Perhaps it was a reservoir, feeding the baths and not a proper lake outside.

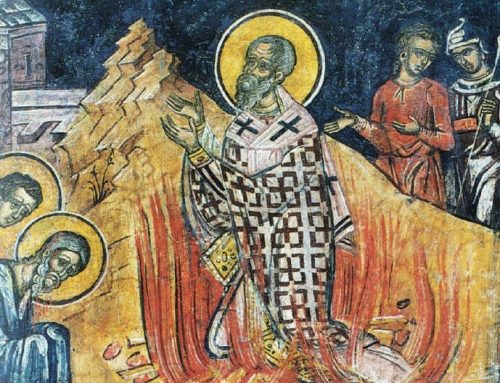

Later a church was built on the site of their martyrdom and it was in this very church that Gregory of Nyssa delivered his discourses in honour of the martyrs.

On this frozen lake, in the very low temperature, the suffering of their naked bodies would have been appalling. To increase the pangs of the victims they were put where they had a clear view of the open door of the baths and in the light they could see the clouds of steam from thecalidarium.

This was a powerful sight for the sufferers since they would only have to take a very few paces to escape their torment and regain that life which was leaving their bodies by the minute. But there was an insurmountable barrier between them: the invisible Christ, whom they would have to deny.Time passed very slowly: none of the condemned left the stretch of ice. The superintendent of the baths was fascinated by the spectacle.

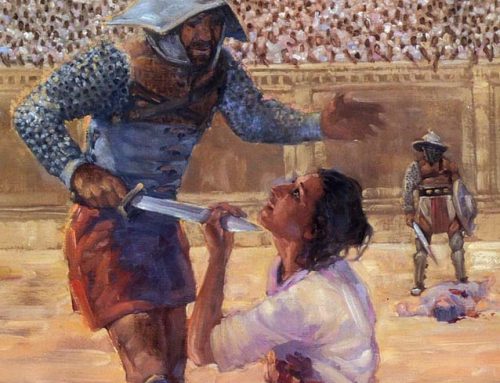

All of a sudden one of the condemned overcome by the cold went towards the illuminated doorway, but there, for a regular physiological reason, hardly had he reached the warm vapour than he died. Seeing this, the superintendent, in a burst of enthusiasm, decided to take the place of the one who had given in, and so restore the number forty. Taking off his clothes, he proclaimed himself a Christian and went on to the ice with the other condemned.

The veneration of the Forty Martyrs was quite popular in the East. But even in the West, by the end of the same century, Gaudentius of Brescia speaks of them because he was well informed about the facts of Orient. However, in Rome a painting of their martyrdom is still preserved in a fresco of the VII-VIII centuries. It is in an oratory adjoining the church of Santa Maria Antiqua in the Roman Forum. (by Giuseppe Ricciotti, L’Era dei Martiri, Coletti edition, Roma, 1953, pp. 268-70).

Leave A Comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.