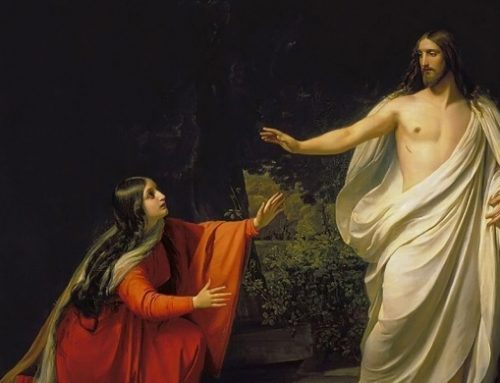

Jesus Christ’s Resurrection is a real event with historical evidence

The Apostles bore witness to what they had seen and heard. In about the year 57 AD, St Paul wrote to the Corinthians: “I delivered to you as of first importance what I also received, that Christ died for our sins in accordance with the scriptures, that he was buried, that he was raised on the third day in accordance with the scriptures, and that he appeared to Cephas, then to the twelve” (1 Cor 15:3-5).

On looking at these facts today to find the objective truth about what happened, the question may arise: Where did the statement that Jesus rose from the dead come from? Was it a manipulation of reality which has had extraordinary repercussions on human history; or is it a real fact that is as surprising and unexpected today as it was then to his stunned disciples? The only way to find a reasonable answer to these questions is by investigating the beliefs of those men on life after death, to see whether the idea of a resurrection from the dead such as they talked about, was something that fitted with their mindset.

To start with, in the Greek world there are references to a life after death, but it had very particular features. Hades is a recurrent concept from Homer onwards. It is the house of the dead, a world of shadows which is a sort of vague memory of the dwelling-place of the living. But Homer never imagined that anyone could actually return to this life from Hades. Plato, from a different viewpoint, had speculated about reincarnation, but he did not think of the real possibility of a body coming back to life again after it had died. In other words, although life after death was sometimes spoken of, the idea of resurrection, in the sense of a return to bodily life in the present world on the part of an individual person, never crossed anyone’s mind.

In Judaism the situation is partly different and partly similar. The “Sheol” referred to in the Old Testament and other ancient Jewish texts was not very different from Homer’s Hades. People in Sheol were as though asleep. But, unlike the Greek notion, there were doors open to hope. God is the One God, both of the living and of the dead, and he has power both in this world and in Sheol.

Triumph over death is possible. In the Jewish tradition, there were signs of belief on the part of some people in some kind of resurrection. They also awaited the coming of the Messiah, but there seems to have been no connection between the two events. For any Jewish contemporary of Jesus, the two notions belonged to very different spheres. They believed that the Messiah would overthrow the Lord’s enemies, restore the Temple worship in all its splendor and purity, and establish the rule of the Lord over the whole world, but they never thought of his rising again after dying: it was something that did not normally enter the imagination of any devout and well-instructed Jew.

To steal the body and invent the story that Jesus had risen with that same body, as an argument to show that he was the Messiah, would be simply unthinkable. On the day of Pentecost, according to the Acts of the Apostles, Peter proclaims: “Let all the house of Israel therefore know assuredly that God has made him both Lord and Christ, this Jesus whom you crucified” (Acts 2:36).

The only explanation for the Apostles’ testimony is that they had seen something they could never had imagined, and which, in spite of their amazement and the mockery they knew they would incur, they felt they had the duty to testify about.

Leave A Comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.