“Remember that Jesus Christ rose from the dead and was descended from david; this is my gospel, in which i suffer even to bonds, as a criminal. but the word of god is not bound. this is why i bear all things for the sake of the elect, that they also may obtain the salvation that is in Christ Jesus, with heavenly glory.” (2tm 2, 8-10)

Among the first Christians at Rome were disciples of St Paul, as is evident from the long list of greetings at the end of the Letter to the Romans. On the Aventine Hill in Rome lived Aquila and Prisca or Priscilla, a married couple of traders who first met St Paul in Corinth. Others who are greeted by name were people from Israel, Greece or Asia Minor who had gone to live in Rome, the capital of the Empire, after hearing St Paul preach the Gospel in their native countries.

The affectionate tone of his greetings reflects the fraternal spirit that existed among these first faithful. Despite their very different origins and social circles, ranging from slaves to members of the nobility, they were all very united. St Josemaría described them as “families who lived in union with Christ and who made him known to others. Small Christian communities which were centres for the spreading of the Gospel and its message. Families no different from other families of those times, but living with a new spirit, which they spread to all those who were in contact with them. This is what the first Christians were, and this is what Christians today have to be: sowers of peace and joy, the peace and joy that Jesus has brought to us.”

Saint Paul’s lodgings in Rome

In this atmosphere of close unity, St Paul’s arrival in Rome must obviously have been a cause of great joy for the Christians there. As mentioned above, some of them owed their faith to him, and all of them had heard of him and were very keen to meet him. In addition, they must have been extremely grateful for the Letter he had written to them in the year 57 or 58. It was natural, then, for them to be so impatient to see him that they went to meet him on the Via Appia. Some of them met him at the Forum of Appius and others at the Three Taverns, 69 and 53 kilometers outside Rome respectively. The Acts of the Apostles notes that on seeing them, Paul gave thanks to God and took fresh heart.

Once he arrived in Rome, about the middle of the year 61, Paul was permitted to live in a private house with one soldier to guard him. Roman citizens had the right to this type of imprisonment, known as custodia militaris, military custody, halfway between custodia libera, supervised freedom, and custodia publica or penal detention.

The prisoner could choose his own place of residence and the soldier who guarded him had to stay with him all the time and put him on a chain whenever he went out of the house. According to an ancient tradition, St Paullived in a hired house near the great bend in the River Tiber at the level of the TiberIsland. It was a densely populated area with a large proportion of Jews. Archaeological evidence shows that many of them were tanners.

On the spot of St Paul’s house, the church of San Paolo alla Regola now stands, the only church dedicated to St Paul within the ancient walls of Rome. As you enter on the right, an architrave bears the inscription Divi Pauli Apostoli Hospitium et Schola – the Lodging and School of the Apostle St Paul. In the same area there has been located a building dating from the imperial era which, like others nearby, had a large barn attached to it.

This matches the description of St Paul’s house found in some second-century documents; the large barn explains how it was possible for St Paul, newly arrived in Rome, to summon to his lodging a large number of Jews living in Rome to announce the Kingdom of God to them.

The result of this encounter was that some of the Jews became believers, but St Paul also met considerable resistance to the Gospel. As a result, he resolved that from then on he would dedicate himself to the Gentiles, because they were ready to listen to the message of salvation.

![]()

En este lugar se ha encontrado un edificio de época imperial que, como otros de la zona, tenía adosado un amplio granero. Corresponde a la descripción de la casa de San Pablo que aparece en algunos documentos del siglo II; la presencia del espacioso granero explicaría cómo fue posible que, casi recién llegado a Roma, el Apóstol pudiera convocar en su alojamiento a un gran número de judíos que vivían en la Urbe para anunciarles el Reino de Dios.

El resultado de aquella larga reunión fue que algunos hebreos creyeron, pero San Pablo también encontró mucha resistencia al Evangelio. Por eso, concluyó que a partir de entonces se iba a dedicar a los gentiles, porque ellos sí escucharían el mensaje de salvación.

St Paul remained in that house for two years, spreading the fire of his faith and love for Christ in the very heart of imperial Rome. A prisoner, or at any rate deprived of freedom of movement, he was nevertheless convinced that for those who love God, all things work together for the good, and so was able to write to the Philippians,

“I want you to know, brethren, that what has happened to me has really served to advance the gospel, so that it has become known throughout the whole praetorian guard and to all the rest that my imprisonment is for Christ; and most of the brethren have been made confident in the Lord because of my imprisonment, and are much more bold to speak the word of God without fear.”

This missionary activity on the part of the early Church in Rome was blessed by God with abundant fruit. The Christians did personal apostolate and made converts, and during his captivity there, St Paul was already able to send to other churches greetings from Christians living in the Emperor’s own house (Phil 4:22).

These “saints of Caesar’s household” were probably civil servants working in the administration of the Empire. The Christians at Philippi must have been delighted to see that the Gospel had also reached those circles, from which so much could be done to change society.

The place of Saint Paul’s martyrdom

The end of the Acts of the Apostles tells how Paul stayed for two whole years in his hired house, and received all those who came to see him. He preached the Kingdom of God and taught everything about the Lord Jesus Christ.

Everything seems to indicate that at the end of that period, the maximum allowed in Roman law for custodia militaris, St Paul regained his freedom and was able to leave Rome and travel to other places. In his letter to the Romans years before, he had written of his intention of going to Spain to preach the Gospel there, and perhaps he did this in the year 63.

From what he writes in his last letters, those to Timothy and Titus, it may be deduced that between 63 and 66 or 67 AD, St Paul travelled through different cities in Greece and Asia Minor. Meanwhile, during the summer of 64, there had begun Nero’s cruel persecution against the Christians at Rome, which then spread to other parts of the Roman Empire. Paul may have been captured at Troas, since he left that city without taking so much as his travelling-cloak with him. After his arrest he was taken to Rome once more, guarded by a number of soldiers.

This second imprisonment was much harsher than the first. It was custodia publica, meaning that he was kept in prison as a common criminal. Paul was old and tired by this time, and he found it hard to endure the separation from his closest fellow-workers. Only Luke, the faithful doctor, remained with him, and St Paul wrote to Timothy to come to Rome as soon as possible.

Some of his disciples had abandoned him in his hour of need, and he was hurt most of all by the desertion of Demas, who left him “for love of this present world”. “For a trifle, and for fear of persecution, this man, whom Saint Paul had quoted in other epistles as being among the saints, had betrayed the divine enterprise. I shudder when I realise how little I am: and it leads me to demand from myself faithfulness to the Lord even in events that might seem to be indifferent – for if they do not help me to be more united to Him, I do not want them.”

Completely deprived of his freedom, and cut to the quick by these infidelities, St Paul suffered, as only those whose love is measureless can suffer. At the same time, his total trust in God filled him with courage, and he exclaimed,

“I am suffering and wearing fetters like a criminal. But the word of God is not fettered. Therefore I endure everything for the sake of the elect, that they also may obtain the salvation which in Christ Jesus goes with eternal glory.”

The Christians of Rome tried to keep close to St Paul and to minister to him in so far as they could under the persecution. St Paul sent their greetings to Timothy, with Eubulus, Pudens, Linus and Claudia mentioned by name. At the time of writing to this much-loved disciple, Paul had had a first hearing at the tribunal and had had his trial postponed. He knew that he had just a few months left, and so he urged Timothy to come quickly, before the winter. However, Paul entertained no doubts as to the final sentence.

“I am already on the point of being sacrificed; the time of my departure has come. I have fought the good fight, I have finished the race, I have kept the faith. Henceforth there is laid up for me the crown of righteousness, which the Lord, the righteous judge, will award to me on that Day, and not only to me but also to all who have loved his appearing.”

We do not know whether Timothy arrived in time to give a last embrace to the man to whom he and his family owed their faith. Paul was condemned to death and executed ten days after the sentence, as the law laid down. As a Roman citizen he was beheaded, with no public watching, outside the city walls.

The place of St Paul’s martyrdom was the district that is now known as the EUR, in the south of Rome. The inhabitants of the city referred to it as ad aquas salvias. A Christian cemetery was located there from the third century, and a church from the fourth or fifth. According to ancient traditions, St Paul was beheaded near the main road, on a raised piece of ground by a pine-tree; when his head fell onto the sloping ground it rebounded three times, and a spring of water burst out miraculously each time. For this reason, the church later built on the spot was given the name of St Paul ad tres fontes, at the three fountains.

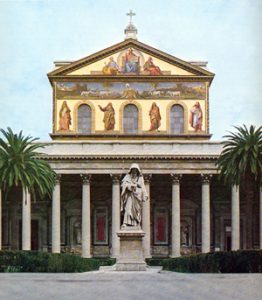

The Tomb in the Basílica of Saint Paul Outside the Walls

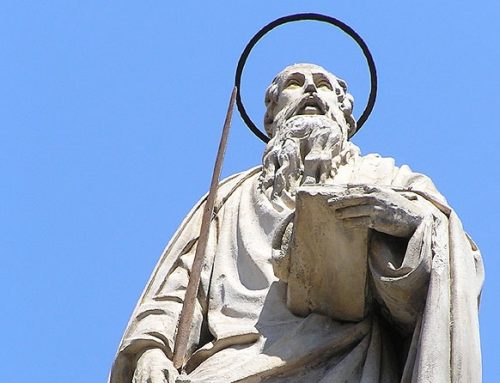

St Paul’s body was buried in a cemetery located on the Via Ostia. The Christians built his tomb as a trophaeum, a modest monument similar to that at the tomb of St Peter. The priest Gaius, at the end of the second century, spoke of the monuments of the Apostles who had founded the Church at Rome that were on the Vatican Hill and the Via Ostia.

St Paul’s body was buried in a cemetery located on the Via Ostia. The Christians built his tomb as a trophaeum, a modest monument similar to that at the tomb of St Peter. The priest Gaius, at the end of the second century, spoke of the monuments of the Apostles who had founded the Church at Rome that were on the Vatican Hill and the Via Ostia.

After the Edict of Milan in 313 AD, the Emperor Constantine had a basilica built to guard and venerate the tomb of the Apostle of the Gentiles. It was not a very large one, but was enlarged at the end of the fourth century with the construction of the Basilica of the Three Emperors, so named because the work was begun by Emperor Valentinianus II, continued by Emperor Theodosius, and completed by Emperor Arcadius. The heart of this second basilica, like the first, was the tomb of St Paul: in both cases, the altar was placed immediately above the tomb.

The present basilica was built in the nineteenth century, after the previous one was destroyed by fire in 1823. During the construction work the area of the tomb itself was uncovered, and two architects made some sketches of its position and appearance. Apart from these rather rough sketches, little more was known about the tomb, until in December 2006 news was published of the finding of a marble coffin, situated in the Confessio or area beneath the altar of the Basilica.

It is thought that it was in this coffin that St Paul’s mortal remains were placed. The simplicity of the coffin contrasts with the much more artistic design of other coffins which had been found in the vicinity in the mid-nineteenth century. The difference in quality may be attributed to the fact that the Emperors, knowing that it contained the Apostle’s remains, preferred to leave it as it was and not change it for a richer one.

Shortly after the news of the finding of this coffin had been made public, on December 14, 2006, His Beatitude Christodoulos, Archbishop of Athens and All Greece, came to pray in the Basilica. That same day, he had visited the Pope in the Vatican. They exchanged gifts expressive of their desire to achieve unity: a picture of the Virgin Mary as Panaghia, all holy, and an icon with the classic image of Sts Peter and Paul embracing. This was the first time that a Primate of Greece had ever paid an official visit on the Pope. This encouraging news undoubtedly stimulates us to pray still harder for Christian unity. Ecumenism is a task for all Christians to work at.

Leave A Comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.