What was the reaction of the first Christians to the world in which they were immersed? We may be tempted to explain the spread of the Gospel in terms of marvels and miracles. Their faith was the “miracle” that attracted people from all classes, conditions and cultures. Their faith, and their love for Christ. What was the reaction of the first Christians to the world in which they were immersed? We may be tempted to explain the spread of the Gospel in terms of marvels and miracles. Their faith was the “miracle” that attracted people from all classes, conditions and cultures. Their faith, and their love for Christ.

The Fire of the First Christians

What was the reaction of the first Christians to the world in which they were immersed? We may be tempted to explain the spread of the Gospel in terms of marvels and miracles. Their faith was the “miracle” that attracted people from all classes, conditions and cultures. Their faith, and their love for Christ.

It is still a few hours till dawn. A man is walking along the shore of the beach, contemplating the sea. He is famous in many intellectual circles. Soon he comes upon another person in that deserted place—an old man. The intellectual is surprised to find someone else here at this hour of the morning, but he says nothing. The old man notices his hesitancy, and starts a conversation with him. He tells him he is waiting for some family friends, who are out on the sea in a boat. The conversation continues. The intellectual speaks about many different topics: culture, politics, religion. He likes to talk. The old man listens politely; when he makes a comment he does so from a Christian point of view. Perhaps on other occasions the intellectual would have ridiculed him or cut him short. But the old man’s simplicity is disarming. The intellectual is unable to accept all his ideas, but he realizes that the two of them have a lot in common. He finds the old man’s humble faith attractive. Hours go by. They say good bye. They never meet again.

The intellectual will never forget that meeting. A few months later, he comes to realize that only the old man’s words hold the answer to his yearnings for the truth. A chance encounter has brought him to the faith, opening up a much broader horizon than all his previous ideas had permitted. A short time later, Justin the Philosopher will be baptized and become one of the greatest Christian apologists.[1]

Perhaps something similar has happened to our friends or even to us. The story of St. Justin is quite relevant today, since the answers to the questions that all men and women ask—the meaning of life, the possibility of happiness, the way to reach it, the reason for suffering—are found only in Christ. But it is not immediately apparent that happiness and fulfillment are found in the Cross. Perhaps that is why at times we divert our attention from this question. We seek to flee suffering at any cost, but suffering is unavoidable. We seek success, the security of money, pleasure—but these prove false in the end, and lead only to boredom and disgust. Finally the only thing that remains is the loneliness the prodigal son experienced, the destitution of one who tries to live without God.[2]

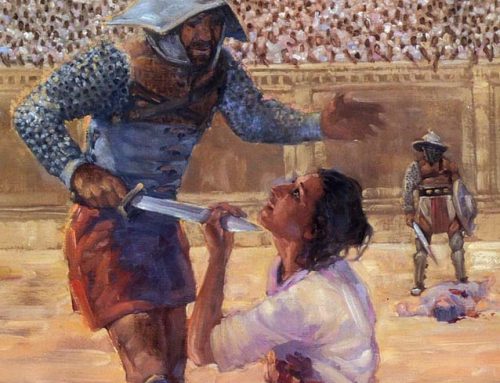

When we read St. Augustine’s Confessions or the lives of the early converts, we see that they have the same basic concerns as people today. The same anxieties, the same solutions, the same alternatives, the same sole answer: Christ. Some deny this, claiming that people back then were unable to distinguish reality from fiction, and that belief in God is now untenable in view of “progress” and a modern understanding of freedom. But this way of looking at the first Christians—and their fellow citizens—fails to do them justice. In ancient Rome there were also many “modern” people who took advantage of progress to maximize their pleasure and justify in the name of freedom their own selfishness. The first Christians, in responding to grace, confronted the same difficulties as we do. In fact the difficulties may have been objectively greater, since they lived in a world completely foreign to Christian ideas. Although technically and culturally superior to any previous age, it was a world in which words such as “justice” and “equality” were reserved for very few; where crimes against life were commonplace, and entertainment included watching others die. People sometimes speak about the modern-day world as “post-Christian,” in a pejorative sense. But this way of speaking overlooks the fact that even those who refuse to accept Christ’s message base their own lives on the positive human values Christianity has fostered. The common ground is obvious to anyone with good will. In a certain sense, reality after Christ is Christian.

The piety of the first Christians

What was the reaction of the first Christians to the world in which they were immersed? Sometimes we are tempted to explain the expansion of the Gospel in terms of marvels and miracles. We could even fall into the mistake of thinking that, when miracles are scarce, the only recourse is to put up with the errors around us. But that would be to forget that Christ is the same yesterday, today and always, and that his arm has not been shortened. It would also mean forgetting that most of the early Christian communities never witnessed any extraordinary events. Their faith was the “miracle” that attracted people from all classes, conditions and cultures. Their faith, and their love for Christ.

The first Christians were aware that they possessed a “new life.” “The simple and sublime certainty of their Baptism”[3] had given them a new reality: nothing could ever be the same again. They had been granted a share in Jesus’ love for all men and women. God lived in them, and as a result the first Christians tried to seek God’s will in every moment; they tried to reflect in their actions the same acceptance the Son showed to the plans of his Father. Through their daily life, through its heroic coherence—heroic often only because of its unfailing constancy—Christ infused life into the environment around them. They were able to be God’s instruments because they always tried to act as Jesus himself did. St. Justin attributed his faith to the old man he met on the beach, even though his conversion came later. Priscilla and Aquila saw in Apollos a person who could come to have great faith in Christ. Today we realize that the results of such meetings are impossible to gauge. We cannot conceive of the apologists without the figure of St. Justin, while Apollos played a key role in Christianity’s expansion. And it all depended on a single moment. What would have happened if the old man hadn’t taken the initiative and started a conversation with Justin? Or if Aquila and Priscilla had stopped to admire the oratorical skills of Apollos and then continued on their way? We will never know. What we do know is that they responded to the action of the Holy Spirit, who led them to see an opportunity to spread the faith, and God made their docility very fruitful. We see in them what our Father wanted all his children to be, and all Christians: “Each one of you must try to be an apostle of apostles.”[4]

What enabled them to correspond to the motions of the Holy Spirit in their soul was, in the first place, their intense life of piety. They set aside specific times during the day to talk more intimately with God, not leaving it to chance. They realized that this was the only way they would be able to find our Lord during the rest of their day.

We have many texts that show how the first Christians lived their faith. When they got up in the morning, they thanked God on their knees. During the day they prayed the Our Father three times. The Fathers of the Church and the first ecclesiastical writers show how they connected its words to their daily activities. Among other things, this prayer brought home to them the reality of their divine filiation. When praying for their enemies, they asked themselves how they could show God’s love to them. When asking for their “daily bread,” they saw a relationship to the Blessed Eucharist, giving thanks for this great gift; in the same words they also saw the need to be detached from earthly goods, not wishing for more than was necessary nor being overly concerned about what they lacked. The Our Father became a synthesis of the entire Gospel and the rule of Christian life. The times they chose to pray it reminded them of the mysteries of the faith and the need to strive to become like Jesus all throughout their day, hour by hour: “At the third hour the Holy Spirit descended on the Apostles…at the sixth hour our Lord was crucified; at the ninth hour he washed away our sins with his blood.”[5] The catechesis and formation they received never separated the Christian mysteries from their lives.

Many Christian faithful fasted on Wednesdays and Fridays, the dies stationis, the “station days.” They continued working, but their whole day was marked by a spirit of watchfulness, praying in particular for their fellow citizens. Like soldiers on guard, whenever they practiced this custom they saw themselves as keeping watch in the presence of their Lord. This pious practice also had repercussions on the environment around them. “Calculate the amount you would have spent on the meal you were to eat, and give it to a widow, an orphan or someone else in need.”[6] It is moving to see the bond, throughout the Christian centuries, between true piety and charity.

The Eucharist held a special place in this regard. The first Christians’ eagerness for the word of God, for prayers and for the breaking of the bread[7] was not limited to Sundays. Texts from the first Christian writers tell us that some of the faithful received Holy Communion during the week, which at times involved a considerable effort in order not to break their voluntary fasts. Any little sacrifice was seen as nothing as long as it strengthened their union with Jesus. They knew that the more closely united they were to Christ, the easier it would be to discover what God expected of them and to discern the opportunities he had prepared to bring true happiness to so many men and women.

They did not view these practices of piety as “obligatory impositions” of the faith. They were the logical way to respond to the gift they had received. God had given himself for them. How could they fail to converse with him, to seek him out? Therefore they were not content with the bare minimum, but did everything possible to give honor to God and to speak with him.[8] These norms of piety (as we could call them) gave them the strength needed to make Christ visible in their actions, to live as contemplatives, knowing that he wanted to use each of their actions to proclaim the Kingdom of God. They never forgot that many great things depended on whether they lived their lives as God wants.[9]

With the strength of charity

A life of piety is inseparable from an incisive apostolate. In some cases, the friends of the first Christians noticed the changes in their way of life: the dignity of the Christian condition is incompatible with many actions which until then, like now as well, were considered “normal.” Christians took advantage of this contrast to explain the reason for their hope and their new attitude. They showed how their outlook was more in keeping with human dignity, and how their faith did not negate what was good in the world: “I do not bathe on the eve of the Saturnalia, lest I should lose both night and day; yet I bathe at a proper and healthy hour, and preserve my warmth and color…I do not sit down to eat in public at the feast of Bacchus…yet when I do sit down to eat, I eat of your abundance.”[10] They explained how this allowed them to keep their heart for God, because “if we flee from thoughts, much more so will we reject deeds.”[11] Thus they rejected the sophistic stance of a purely exterior morality. For it is what comes out of the heart that defiles a man.[12]

At times their conversion to Christianity would not be noticed, at least initially. Many of the first Christians, before their baptism, were known by their upright life: St. Justin, the Consul Sergius Paulus,[13] Pomponia Graecina,[14] the Senator Apollonius,[15] Flavius,[16] and many others who could be mentioned. Roman historians list some illustrious names, but the greater part of the first Christians were ordinary people who saw the truth in our Lord’s message, under the influence of grace. The fact of finding the faith when already adults gave added importance to their professional work and social relations: it was there that Christ was going to act in andthrough them. It was never a matter of deciding to separate themselves from the society in which they had grown up and which they loved. They of course rejected anything that could offend God. But they were diligent in fulfilling all their duties and knew that by their actions they were helping to bring about a more just world. We have many testimonials to this fact, but perhaps the best proof of their attitude was the first Christians’ incisive apostolate. Behind the history of each conversion we find a person whose deeds reflect a good and true choice, a man or woman who confronts life with new energy and joy.

When the moment came to act, the first Christians did not waste time over false dilemmas regarding what was public and what was private. They simply lived their lives, the very life of Christ. This attitude clashed with the mentality of the time, when many people viewed religion as an instrument for attaining harmony within the state. We see this tension, for example, in St. Justin’s martyrdom. The prefect Rusticus was unable to accept or grasp the martyr’s words about personal responsibility and initiative. “Each one meets where he wishes. No doubt you think that we gather in the same place, but it is not like that…I live with someone named Martin, near the Baths of Timothy. And if someone wants to come and see me, it is there that I would tell him the words of truth.”[17] Their apostolic activity was a result of enjoying the full freedom and initiative of God’s children. The great social changes they helped bring about were always the result of a great number of personal changes.

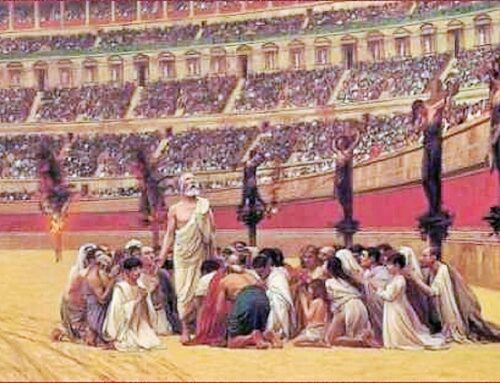

Misunderstandings were a spur for the first Christians to show their faith with deeds. Their love for God was shown in martyrdom, seen as “giving witness.” While physical martyrdom was viewed as the supreme testimony, the majority of Christians knew that their lives had to reflect a spiritual martyrdom, with the same love that inspired the martyrs. For centuries the words “martyr” and “witness” were synonymous, referring to the same reality. Our first brothers and sisters in the faith knew that acting in a Christian way would make it easier for people to understand the Gospel and that inconsistent behavior would lead to scandal. “When the gentiles hear God’s words from our lips they are amazed by the beauty and greatness contained in them; but if they see that our deeds are unworthy of our words, they straight away begin to blaspheme, saying that it is all just a false and deceptive story.”[18] Benedict XVI has reminded us of the need to make Christ’s love manifest to all: “Love of neighbor, grounded in the love of God, is first and foremost a responsibility for each individual member of the faithful.”[19] What a marvelous responsibility: making present here and now the love that mankind always needs![20] The first Christians showed others this love by their social concern, their professional honesty, their clean life, their friendship and loyalty. In a word, by their consistent life: “We are consistent always and in everything, and in harmony with what we are, since we obey our nature and do not go against it.”[21]

Thus it is easy to understand why Saint Josemaria encouraged his daughters and sons to imitate the first Christians. We want to live as they did: “meditating on the doctrine of our faith until it becomes part of us; receiving our Lord in the Eucharist; meeting him in the personal dialogue of our prayer, without trying to hide behind an impersonal conduct, but face to face with him. These means should become the very substance of our life.”[22] Then our work and our daily lives will manifest who we are: Christian citizens who want to correspond fully to the joyful demands of our faith.[23] We will experience “the amazement of the disciples as they contemplated the first-fruits of the miracles being worked by their hands in Christ’s name,” and we will be able to say like them, “What an influence we have on the environment!”[24]

1. Cf. St. Justin, Dialogus cum Tryphone, 2.

2. Cf. Lk 15:16.

3. St. Josemaria Escriva, Conversations, 24.

4. St. Josemaria Escriva, The Way, 920.

5. St. Cyprian, De Dominica oratione, 35.

6. Hermas, The Shepherd, Comparison V, 4.

7. Cf. Acts 2:42.

8. Cf. Tertullian, De Oratione, 27.

9. Cf. St. Josemaria Escriva, The Way, 755.

10. Tertullian, Apologeticum, 42.

11. Athenagoras, Legatio pro christianis, 33.

12. Cf. Mt 15:18-19.

13. Cf. Acts 13:7.

14. Cf. Tacitus, Annales, 13, 32.

15. Cf. Suetonius, Vita Domitiani, 10, 2.

16. Cf. Suetonius, Historia Romana, 67, 14.

17. Martyrium S. Iustinii et sociorum, 75.

18. Pseudo-Clement, Homily [Secunda Clementis], 13.

19. Benedict XVI, Enc. Deus caritas est, 25 December 2005, no. 20.

20. Cf. Ibid., no. 31.

21. Athenagoras, Legatio pro christianis, 35.

22. Christ is Passing By, 134.

23. Cf. Ibid.

24. St. Josemaria Escriva, The Way, 376.

Leave A Comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.