Christianity began and developed within the political and cultural framework of the Roman Empire. For three centuries, the pagan empire persecuted the Christians because their religion represented a ‘rival’ form of universalism and forbade its adherents to offer religious worship to the emperor.

1. Introduction: Roman Empire and Christianity

The birth and early development of Christianity took place with the political and cultural framework of the Roman Empire. It is true that pagan Rome persecuted the Christians for three centuries; but it would be wrong to see the empire as only a negative factor in the spread of the gospel. The fact that Rome had imposed unity on the Greco-Latin world meant that over a huge area, under a single supreme authority, peace and order reigned. This situation lasted until well into the third century and good communications among the various parts of the empire made it easy for ideas to circulate. The Roman roads and the sea-routes of the Mediterranean provided channels for the good news of Christianity to spread over the whole Mediterranean area.

2. The First Converts

A common language – based on Greek, at first, and on Greek and Latin, later – made it easier for people to communicate and understand one another. Paganism was in crisis, very many spiritually sensitive people were searching for religious truth and were predisposed to the gospel. These factors, undoubtedly favored the spread of Christianity.

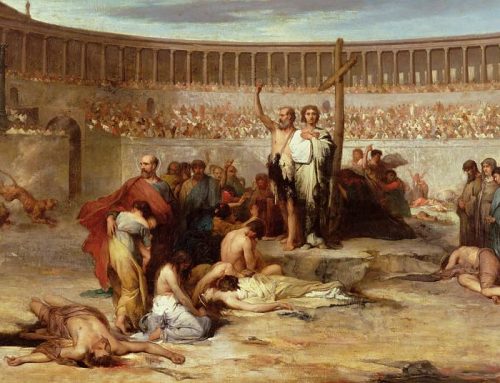

But there were also very serious objects in the way of people embracing the Christian faith. For Christians of Jewish background it meant breaking with their community of origin – which now regarded them as deserters and traitors. Gentile converts, especially those belonging to the upper classes, encountered similar difficulties: their faith did not allow them take part in a series of traditional pagan-religious practices involving worship of Rome and the emperor, yet these practices were part and parcel of a citizen’s everyday life and they were a conventional sign of loyalty to the empire. Hence the accusations often leveled against the Christians that they were ‘atheists.’ This was a reason why they were threatened with persecution and martyrdom – a threat which hung over them for centuries and meant that to become a Christian involved taking risks; and demanded a high degree of moral courage.

What caused the great confrontation between the pagan empire and Christianity? The Christian religion encouraged people to respect and obey lawful authority. ‘Render to Caesar the things that are Caesar’s, and to God the things that are God’s’ (cf. Mt 22:15-21) was the principle given by Christ himself. The Apostles developed this teaching: ‘Let every person be subject to the governing authorities. For there is no authority except God.’ (Rom 13:1), wrote St. Paul to the faithful at Rome; and St. Peter exhorted the disciples to ‘Fear God. Honor the emperor’ (1 Pet 2:17). The empire, for its part, was liberal in religious matters and easily tolerated new forms of worship and foreign divinities. The collision and the break occurred because Rome tried to get its Christian subjects to do something they could not do – render it the religious homage of adoration which may be given lawfully to God alone.

3. The Persecution of Nero

The circumstances surrounding the first persecution – Nero’s – had enormous effects, despite the fact that this persecution does not seem to have extended further than the city of Rome. The Christians were officially accused of a heinous crime – the burning of the city – and this created a widespread public opinion hostile to the new religion.

The historian Tacitus regarded Christianity as ‘a pernicious superstition’; Suetoniusdescribed it as ‘novel and mischievous’; Pliny the Younger as ‘depraved and extravagant.’Tacitus went as far as calling the Christians enemies of mankind. Therefore it is not surprising that ordinary people attributed to Christians all sorts of monstrosities such as infanticide and cannibalism, etc. According to Tertullian, ‘Christians to the lions’ became the obligatory catch-cry of every riot.

4. The Development of Christianity in the first four centuries

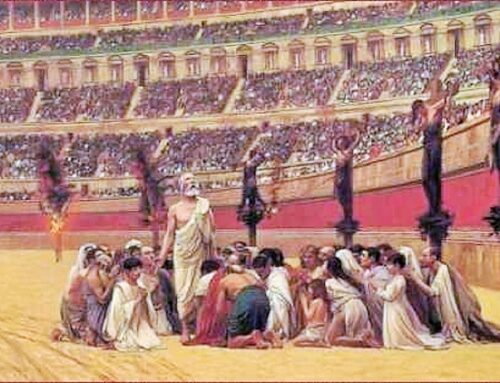

From the first century on, Christianity was regarded as an ‘unlawful superstition’, which meant that the mere profession of Christian belief – ‘bearing the name of Christ’ – was a crime. This explains why many anti-Christian acts of violence in the second century originated not so much in actions of emperors or magistrates as in popular agitation and denunciation. Consequently, persecution during this period was not a general or continuous phenomenon; the Christians sometimes enjoyed long periods of peace, without this meaning that they felt any real security under the law: at any moment they could find themselves victims of violence.

The ambiguous attitude of certain second-century emperors is reflected in Trajan’s famous reply when Pliny, the governor of Bithynia, consulted him on what policy he should adopt towards Christians. Trajan replied that the authorities should not take the initiative in seeking out Christians or pay any attention to anonymous informers, but that they should act whenever they received denunciations in the proper form and should condemn and execute those Christians who did not recant and who refused to sacrifice to the gods. Tertullian – a Christian apologist and a skilled lawyer – exposed the absurdity of Trajan’s reply: ‘If they are criminals,’ he says referring to the Christians, ‘why not hunt them down?; and if they are innocent, why punish them?’

In the third century, persecution took a different form. In the attempt to re-establish the empire after the period of ‘military anarchy’ – a period of serious political upheaval – part of the official policy was to restore the cult of the gods and of the emperor as a test of subjects’ loyalty to Rome and its sovereign. The Christian Church came to be seen as a powerful enemy because the faithful were forbidden to engage in this form of worship. This gave rise to a new wave of persecution, this time originated by the authorities – a much more systematic persecution than therefore.

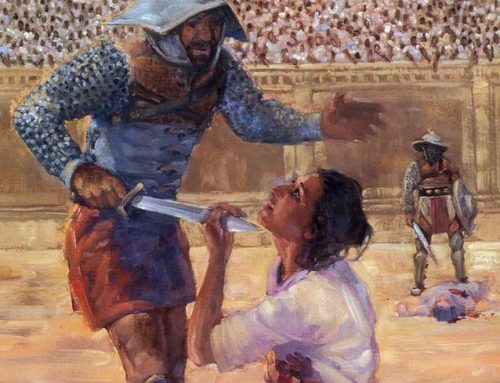

5. The Persecution of Decius

The first of these great persecutions stemmed from an edict of Decius (c. 250) ordering all inhabitants of the empire to offer public, officially supervised sacrifice in honor of their national gods. Decius’ edict took the Christians completely by surprise (Christians were now quite numerous and had become somewhat easygoing after a long period of peace). The result was that, although there were many martyrs, many not very committed Christians did offer public sacrifice or at least obtained the libellus stating that they had offered sacrifice; their re-integration into the Christian community later gave rise to controversies within the Church.

However, the experience they underwent helped to stiffen their resolve and when, a few years later, Emperor Valerian (253-260) launched another persecution, Christian resistance was much firmer: they were many martyrs and very few Christians who proved unfaithful (these were called the lapsi).

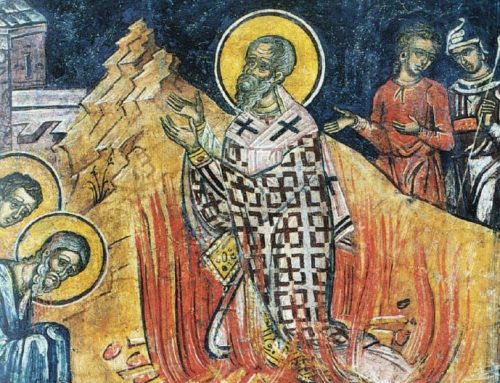

6. The persecution of Diocletian

The severest persecution was the last one, which took place at the beginning of the fourth century, in the context of the great reform of Roman institutions carried out by Emperor Diocletian. The new system of government established by the founder of the later empire was a tetrarchy – government by an ‘imperial college’ of four, among whom was divided the administration of the vast Roman territories. Under the tetrarchy, traditional religion was given a very important role in the regeneration of the empire, yet despite thisDiocletian did not persecute the Christians during the first eighteen years of his reign. A number of factors, not the least the influence of Caesar Galerius, played a part in setting off this last and worst persecution.

Four edicts against Christians were promulgated between February 303 and March 304, aimed at wiping out Christianity and the Church once and for all. The persecution was violent in the extreme and made many martyrs in most provinces of the empire. Only Gaul and Britain – governed by Caesar Constantius Chlorus, who was sympathetic towards Christians and the father of the future emperor Constantine – remained practically untouched. At the end of the day the result was absolute failure. After his abdication Diocletian lived long enough to witness, from his retreat at Salonae in his native Dalmatia, the epilogue of the persecution era and the beginning of an epoch of freedom for the Church and for Christians.

Source: Jose Orlandis (A Short History of the Catholic Church, 2001)

Leave A Comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.