“Who shall separate us from the love of Christ? Shall tribulation, or distress, or persecution, or hunger, or nakedness, or danger, or the sword?” (Romans 8, 35)

1.1. A new and malevolent superstition

The first instance of the Roman State taking action against Christians arose in the reign of the Emperor Claudius (41-54 A.D.). The historians Suetonius and Dio Cassius tell us that Claudius had to expel the Jews because they were continually arguing among themselves about a certain Chrestos. “Here we have first mention of the response to the Christian message in the community of Rome,” comments Karl Baus.

The historian Gaius Suetonius Tranquillus (70- ca.140) was a high-ranking official at the imperial courts of Trajan and of Hadrian. He was a scholar and counsellor of the emperors. He justified this and future actions of the State against Christians defining them as a “new and malicious superstition”; very harsh words.

As a “superstitio“, Christianity was linked to “magia“. For the Romans it was the same as the irrational practices which magicians and witches of evil character used to deceive the ignorant populace who had no training in philosophy. Magic was against reason and was common knowledge as opposed to philosophical knowledge. The accusation of magia (witchcraft), as well as that of insanity was a weapon with which the Roman State branded and suppressed new and suspect groups in society, such as Christianity.

The word malefica (=bringer of evil) caught the popular and suspicious imagination of the populace which viewed this (and everything new) as intrinsically dangerous. It was therefore the cause of evil and inseparable from plague, flood, famine and invasion by the barbarians.

1.2. Nero and the Christians as seen by the historian Tacitus.

In the year 64 a fire destroyed 10 of the 14 wards of Rome. The emperor Nero, accused by the people of being the instigator of the fire, threw the blame on to the Christians. He began the first great persecution which lasted until 68 and saw perish, among others, the apostles Peter and Paul.

The great historian Tacitus Cornelius (54-120), senator and consul, described these events when, in the reign of Trajan, he wrote his Annals. He accused Nero of having unjustly attacked the Christians, but declared himself convinced that they merited the most severe punishments because of their superstitions from which sprang every nefarious deed. Thus he did not even share in the compassion experienced by many people in seeing them tortured . Here is the famous quotation from Tacitus:

“To cut short the public outcry, Nero had to find someone guilty, and blamed a race of men despised for the perversity of their rites and commonly called Christians. The name comes from Christus (Christ), who was put to death when Pontius Pilate was pro-Consul and Procurator of Judea. Now, this pernicious superstition has broken out anew, not only in Judea, the place of origin of this scourge, but even in Rome, where all that is shameful and abominable comes together and is accepted.

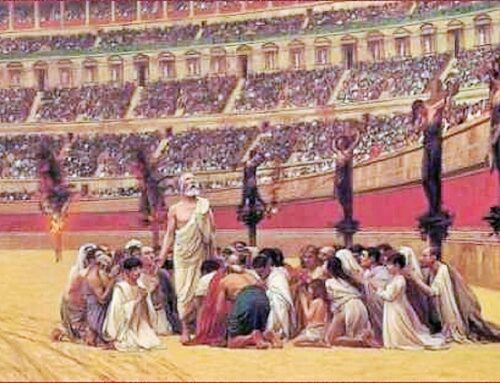

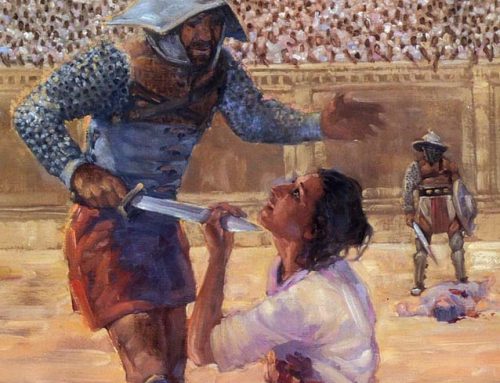

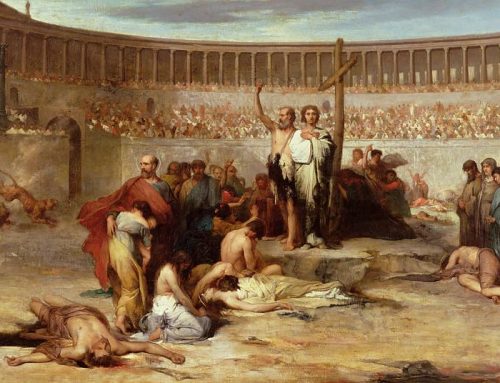

At first were arrested those who openly confessed their belief. Then, after their accusation, a great multitude were imprisoned not just accused of having caused the fire, but because they were regarded as being burning with hatred against the human race.They were put to death with refined cruelty, and Nero added scorn and derision to their sufferings. Some were clad in the skins of wild beasts and thrown to the dogs to be devoured; others were nailed to the cross, others burned alive, and still others covered with inflammable material which was then set on fire to serve as torches after sunset. Nero allowed his gardens (on the Vatican hill) to be used for this spectacle, which also included circus games. As he proclaimed the opening of the circus games, he himself, driving a chariot and dressed as a charioteer, mingled with the crowds.

Although these punishments were against a blameworthy people who merited such original torments, there arose a sense of pity, since they had been sacrificed not for the common good but from the cruelty of the tyrant.” (XV,44)

Thus the Christians were believed by Tacitus as well to be a despicable people, capable of horrendous crimes. The worst evil doings attributed to Christians were ritual infanticide (they spoke of the Lord’s Supper, the Eucharist, as the killing and eating of a child !) and incest (clearly a travesty of the kiss of peace “between brothers and sisters” which occurred in the celebration of the Eucharist). These accusations, based on popular gossip, were thus sanctioned by imperial authority which persecuted and condemned Christians to death.

From this time on (Tacitus maintains) there was added to the burden of Christians, the accusation that they hated the human race. Pliny the Younger, ironically, writes that with a similar accusation anyone could from now on be condemned.

1.3. The accusation of atheism

We have scarce references of the persecution which struck the Christians in the year 89 under the emperor Domitian. Of particular importance is the information given by the greek historian Dio Cassius, who became a praetor and consul in Rome. In book 67 of his Roman History, he tells us that under Domitian they were accused and condemned “for atheism” (ateòtes) the consul Flavius Clemens and his wife Domitilla, and with them many others who “had adopted the practices of the Jews”.

The accusation of atheism, at this time, was thrown at those who did not consider as supreme deity, the imperial majesty. Domitian, strictest restorer of centralised authority, arrogated to himself the highest worship, as centre and guarantor of “human civilisation”.

It is worth noting that an intellectual like Dio Cassius designated as “atheism” the refusal to worship the emperor. It meant that in Rome there was no concept of God separate from that of the imperial majesty. Those who thought differently were regarded as gravely dangerous to “human civilisation”.

[…] The persecutions of the first century: early Christian writings… “As a “superstitio“, Christianity was linked to “magia“. For the Romans it was the same as the irrational practices which magicians and witches of evil character used to deceive the ignorant populace who had no training in philosophy. Magic was against reason and was common knowledge as opposed to philosophical knowledge. The accusation of magia (witchcraft), as well as that of insanity was a weapon with which the Roman State branded and suppressed new and suspect groups in society, such as Christianity.” *it’s important to note that this was before Constantine adopted Christianity, and other denominations were formed or created. […]