4.1. Persecution by Galerius in the name of Diocletian.

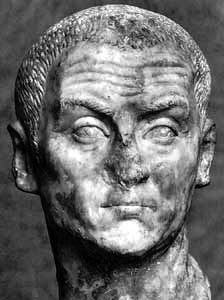

In the first twenty years of the reign of Diocletian we see no molesting of Christians. In 303, with a change of scene, the last great persecution of Christians began. «It was the work of Galerius, the “Caesar” of Diocletian – wrote F. Ruggiero – in 303 he put an end to the prudent policies of Diocletian, which were restrained although he held to traditional feelings, and went over to intransigent and intolerant acts.» Four consecutive edicts (February 303 – February 304) imposed on Christians the destruction of their churches, confiscation of their goods, the handing over of sacred books, torture and even death for those who would not sacrifice to the emperor.

As always, it is difficult to determine what motives induced Diocletian to approve a policy of this kind. We suppose it was pressure from the fanatical pagans who supported Galerius. In a situation of “widespread anguish” (as Dodds calls it), only return to the ancient faith of Rome, according to Galerius and his friends, could save the people and persuade them to make such sacrifices. It required a return to the vetera instituta, i.e. to the ancient laws and traditional roman discipline.

The persecution reached its greatest intensity in the Orient, especially in Syria, Egypt and Asia Minor. To Diocletian who abdicated in 305, there succeeded as “Augustus” Galerius and as “Caesar” Maximin Daia who showed himself more fanatical than his leader.

Only in 311, six days before he died of cancer of the throat, did Galerius grudgingly issue a decree ending the persecution. With this document (which finally signalled the freedom to be Christian), Galerius deplored the obstinacy of Christians who mostly refused to turn to the religion of ancient Rome. He declared that to persecute Christians any more was futile, and he exhorted them to pray to their God for the health of the emperor.

Commenting on this decree, F. Ruggiero, wrote: «The Christians had been an extremely anomalous enemy. For more than two centuries, Rome had sought to absorb them into its social fabric. . . Physically within the civitas Romana, but in many ways outside of it» they had finally brought about «a radical transformation of the civitas itself into something Christian».

4.2. The Profound Revolution

The final systematic persecutions of the Third and Fourth Centuries were as ineffective as the sporadic ones of the First and Second Centuries. The ethnic cleansing invoked and upheld by the Graeco-roman intellectuals was never achieved. Why not ?

Because the indignant accusations of Celsus («Gathering ignorant people, belomging to the vilest population, the Christians bring down the honourable and the noble, and finally go so far as to call people brother and sister without distinction. ») in the long run became the best eulogy for Christians.

It recalled the dignity of each individual, even the lowliest and their equality before God (the most revolutionary point in the Christian message). This had imperceptibly made its way into the consciousness of most individuals and of most peoples whom the Romans had relegated to the positions of born slaves and human garbage.

Leave A Comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.