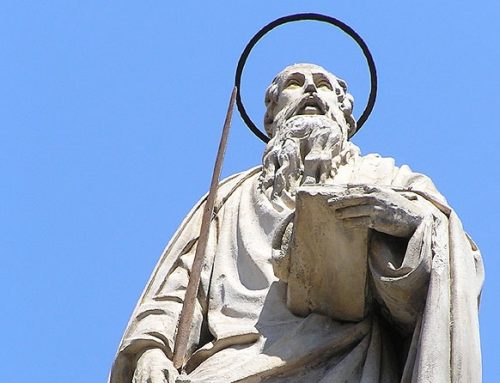

This true protagonist of Christian tradition, just a few years after his death, was celebrated as a “pillar of the Church” by the great theologian and bishop of Constantinople, Gregory Nazianzen (Discourses 26:26). He has always been esteemed as a model of orthodoxy, in the East as well as in the West.

It was no mistake that Gian Lorenzo Bernini placed a statue of him among the four holy doctors of the Eastern and Western Church — together with Ambrose, John Chrysostom and Augustine — which surround the chair of Peter in the apse of the Vatican basilica.

Athanasius was, without a doubt, one of the most important and venerated Fathers of the ancient Church. But above all, this great saint is the passionate theologian of the incarnation of the “Logos,” the Word of God, which — as the prologue of the fourth Gospel says — “was made flesh and lived among us” (John 1:14).

For this reason Athanasius was also the most important and tenacious adversary of the Arian heresy, which at that time was threatening faith in Christ by reducing him to a creature between God and man, following a recurring tendency in history that we still see in various forms today.

Athanasius was most likely born in Alexandria in Egypt, around the year 300, and received a good education before becoming a deacon and secretary of Bishop Alexander of Alexandria. The young cleric worked closely with his bishop, and accompanied him to, and took part in, the Council of Nicaea, the first such ecumenical council, called by the Emperor Constantine in May 325 to ensure the unity of the Church. The fathers of the Nicene Council dealt with many questions, foremost among them, the serious problems that had originated some years before with the preaching of the deacon Arius.

His theory threatened authentic faith in Christ, declaring that the “logos” was not true God, but a created God, a being not quite God and not quite man, but in the middle. And therefore the true God remained inaccessible to us. The bishops in Nicaea responded by emphasizing and establishing the “Symbol of Faith” that, later completed by the first Council of Constantinople, remained in the tradition of various Christian confessions and in the liturgy as the Nicene-Constantinopolitan Creed.

In this fundamental text — which expresses the faith of the undivided Church, and which we still recite today, each Sunday in the Eucharistic celebration — we see the Greek term “homooúsios,” in Latin “consubstantialis,” which means that the Son, the Logos, is “of the same substance” as the Father, is God from God, is his substance. Therefore the full divinity of the Son, which was negated by the Arians, is seen.

Upon the death of Bishop Alexander, Athanasius became, in 328, his successor as bishop of Alexandria. He immediately decided to fight against every compromise resulting from the Arian theories condemned by the Council of Nicaea. His resolve — tenacious and at times very tough, even if necessary — with those who were opposed to his election as bishop and above all against the adversaries of the Nicene Symbol, brought upon him the relentless hostility of the Arians and their supporters.

Despite the unequivocal outcome of the Council, which clearly affirmed that the Son was of the same substance as the Father, these erroneous ideas returned once more to dominate public thought — so that even Arius himself regained popularity, and was supported for political motives by Emperor Constantine and then by his son Constantine II. The latter was not interested in theological truth but rather the unity of the empire and its political problems; he wanted to politicize the faith, making it more accessible — in his view — to all the subjects of the empire.

The Arian crisis, which was thought to be resolved in Nicaea, continued in this way for decades, with difficult incidents and painful divisions in the Church. And five times — during the 30 years between 336 and 366 — Athanasius was forced to abandon the city, living 17 years in exile and suffering for the faith.

But during his forced absences from Alexandria, the bishop was able to sustain and spread — in the West, first in Trier and then in Rome — the faith of the Nicene Council and the ideals of monasticism, which were embraced in Egypt by the great hermit Anthony whose choice of life Athanasius followed closely. St. Anthony, with his spiritual strength, was the most important person in sustaining the faith of St. Athanasius.

After the definitive return to his see, the bishop of Alexandria was able to dedicate himself to religious pacification and the reorganization of the Christian community. He died on May 2, 373, the day in which we celebrate his liturgical feast.

The most famous work of the Alexandrian bishop is the treatise on the “Incarnation of the Word, ” the divine “Logos” made flesh, like us, for our salvation.

In this work, Athanasius says, in a phrase that has become well known, that the Word of God “became man so that we might become God. He manifested himself by means of a body in order that we might perceive the unseen Father. He endured shame from men that we might inherit immortality” (54:3).

In fact, with his resurrection, the Lord made death disappear like “straw in the fire” (8:4). The fundamental idea of the entire theological battle of St. Athanasius was that God is accessible. He is not a secondary God, he is true God, and through our communion with Christ we can truly unite ourselves to God. He truly became “God with us.”

Among the other works of this great Father of the Church — which deal mainly with the events of the Arian crisis — we recall the four letters that he addressed to his friend Serapion, bishop of Thmius, on the divine nature of the Holy Spirit, which was clearly affirmed.

And there are some 30 or so “festal” letters, written at the beginning of every year, to the Churches and monasteries of Egypt to indicate the date of Easter, but moreover to strengthen the ties among the faithful, reinforcing their faith and preparing them for that great solemnity.

Athanasius is also the author of meditative texts on the Psalms, which were vastly distributed, and a text that constituted a “best seller” of ancient Christian literature: the “Life of Anthony,” the biography of St. Anthony the Abbot, written shortly after the death of this saint, while the bishop of Alexandria was in exile, living with the monks of the Egyptian desert. Athanasius was a friend of the great hermit, and even received one of the two sheepskins left by Anthony as his inheritance, together with the mantel that he himself had given him.

The biography of this beloved figure in Christian tradition contributed greatly to the spread of monasticism in the East and the West, as it became very popular and was soon translated twice in Latin and then in other Eastern languages.

The letter of this text, to Trier, is at the center of an emotional telling of the conversion of two ministers of the emperor, which Augustine mentions in the “Confessions” (VIII, 6:15) as a premise of his own conversion.

Athanasius showed that he had a clear awareness of the influence that the figure of Anthony could have on the Christian people.

In fact, he writes in the conclusion of this work: “And the fact that his fame has been blazoned everywhere; that all regard him with wonder, and that those who have never seen him long for him, is clear proof of his virtue and God’s love of his soul. For not from writings, nor from worldly wisdom, nor through any art, was Anthony renowned, but solely from his piety toward God.

“That this was the gift of God no one will deny. For from whence into Spain and into Gaul, how into Rome and Africa, was the man heard of who dwelled hidden in a mountain, unless it was God who makes his own known everywhere, who also promised this to Anthony at the beginning? For even if they work secretly, even if they wish to remain in obscurity, yet the Lord shows them as lamps to lighten all, that those who hear may thus know that the precepts of God are able to make men prosper and thus be zealous in the path of virtue” (“Life of Anthony” 93, 5-6).

Yes, brothers and sisters! We have many reasons to thank St. Athanasius. His life, as that of Anthony and countless other saints, shows us that “those who draw near to God do not withdraw from men, but rather become truly close to them” (“Deus Caritas Est,” 42).

© Copyright 2007 — Libreria Editrice Vaticana

Leave A Comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.