“‘Mary has been taken up to heaven by God in body and soul, and the angels rejoice.’ Joy overtakes both angels and men. Why is it that we feel today this intimate delight, with our heart brimming over, with our soul full of peace? Because we are celebrating the glorification of our mother, and it is only natural that we her children rejoice in a special way upon seeing how the most Blessed Trinity honours her (…) Daughter of God the Father, Mother of God the Son, Spouse of God the Holy Spirit. Greater than she, no-one but God.” (Saint Josemaria Escriva, Christ is Passing By, no. 171)

Faith in this consoling truth leads us to proclaim that “Finally the Immaculate Virgin, preserved free from all stain of original sin, when the course of her earthly life was finished, was taken up body and soul into heavenly glory, and exalted by the Lord as Queen over all things, so that she might be the more fully conformed to her Son, the Lord of lords and conqueror of sin and death.” (Catechism of the Catholic Church, no. 966)

This is the kernel of the Church’s teaching on the final mysteries of our Lady’s life on earth. Sharing in Christ’s victory, she too has conquered death and now triumphs in the glory of heaven with her whole being, body and soul. The liturgy presents this truth for our contemplation every year on the solemnity of the Assumption of our Lady, August 15; and the memorial of the Queenship of Mary celebrated on August 22 recalls that from the moment she was taken up into heaven, she began to rule over all creation together with her divine Son Jesus, as Queen and Mother.

We know very few details our Lady’s last years on earth. Between the Ascension and Pentecost, Sacred Scripture tells us that she was in the Upper Room or Cenacle (cf. Acts 1: 13-14). Afterwards, she would probably have stayed with St John, to whose filial care she had been entrusted. Scripture does not tell us when or where her Assumption took place. Some very ancient sources say it was in Jerusalem; others, more recent, in Ephesus.

Among the traditions of the Holy City, Jerusalem, are some apocryphal writings generically known as Transitus Virginis (“the passing of the Virgin”) or Dormitio Mariae (“the falling-asleep of Mary”). The latter title represents the notion that the end of our Lady’s life was like a sweet dream. These writings tell that, when the Virgin Mary left this world, the Apostles gathered around her bed and our Lord himself came down from heaven, amidst myriad angels, and took his Mother’s soul; then the disciples placed her body in a tomb and three days later our Lord returned and took her body to reunite it with her soul in paradise. The authors of such writings speak of two different places: the house where her soul left her body, and the tomb from which her body was assumed into heaven.

We find echoes of these testimonies in the teachings of several of the Fathers of the Church. St John Damascene, who died in Jerusalem halfway through the eighth century, gives an account of the Assumption of our Lady into heaven that follows the apocryphal writings, and situates the events in the Upper Room and the Garden of Olives. The Virgin’s body, he says, “was prepared for burial and carried out of Mount Zion, set on the glorious shoulders of the Apostles, and borne, together with her casket, to the heavenly temple. But before this it was led through the city like a beautiful bride, adorned with the matchless splendor of the Spirit; and thus it was taken in procession to the holy Garden of Gethsemane, with angels before it and behind it and covering it with their wings, together with the whole of the Church” (St John Damascene, Homilia II in Dormitionem Beatae Mariae Virginis, 12).

In the Holy City of Jerusalem two churches preserve the memory of these mysteries today: the Basilica of the Dormition of Mary on Mount Zion, a few meters from the Church of the Cenacle; and the Basilica of the Tomb of Mary, in Gethsemane, near the olive-grove where Jesus prayed on the night of Holy Thursday.

The Basilica of the Dormition

In the Mount Zion , the early Church was born; and there, in the second half of the fourth century, a basilica was built which was called Holy Zion and was considered to be the mother of all churches. As well as the Cenacle, the basilica included the place of the “transit of our Lady”, which tradition said took place in a house within the zone. The basilica underwent several destructions and restorations in the following centuries, until only the Cenacle itself remained standing. However, the link between this place and the life of the Blessed Virgin Mary was never forgotten, and in 1910 the German Emperor Wilhelm II obtained land on Mount Zion, and a Benedictine abbey was built there, with a basilica next to it dedicated to the Dormition of the Virgin.

The basilica is constructed, in German Romanic style with Byzantine features, on two levels. The upper floor holds the main church, which is round in shape and crowned by a great dome adorned with mosaics. Around this are set six side-chapels and, on the eastern side, a vaulted apse for the sanctuary, with a half-dome which is also set with a great mosaic. On the lower floor, one’s eyes are drawn to the centre of the crypt, where there is a figure of the Blessed Virgin, lying as though asleep, surmounted by a little cupola supported by pillars. The shrine is surrounded by several chapels, the gifts of different countries or associations.

The Basilica of the Tomb of Mary

The Basilica of the Tomb of Mary stands in the channel cut by the Cedron Brook in Gethsemane, a few dozen meters to the north of the Basilica of the Agony in the Garden. It is also called the Church of the Assumption by the Greek Orthodox and Armenian Orthodox, who share the property, and by the Assyrians, Copts and Ethiopians, who hold certain rights over it.

Two flights of stairs lead down to the venerable tomb: the first, from the street to a lower-level courtyard which serves as the entrance to the church and also leads to the site of the Lord’s Arrest; and the second, within the building, from the doorway of the church to the nave. The reason for the church lying at such a low level is that the Cedron riverbed has risen over the course of the centuries, and also, the building which survives today is the equivalent of the crypt of the early basilica, which may have been built in the fourth or fifth century.

A flood in 1972 necessitated radical restoration work, and while this was in progress archeological excavations were also carried out. These excavations, together with historical sources, suggest that the tomb where, according to tradition, our Lady’s body was laid, was part of a first-century burial site. It had been carved out of the rock and included three different zones. When it was decided to build a basilica to enclose the tomb of the Blessed Virgin, the Byzantine architects adopted a method similar to that employed for the Holy Sepulcher: they cut away all the surrounding rock, removing the other two zones, replaced the roof by a strong supporting dome, and built the church over it.

As happened with other Christian sites in the Holy Land, the invasions which occurred during the first millennium meant that by the time the Crusaders arrived in the eleventh century, this basilica was in a poor state. A community of Benedictine monks from Cluny was established there in 1101, and restoration work began on the basilica. The entrance to the crypt was opened and the stairway extended; two chapels were built on either side of the stairway; the tomb of the Virgin was embellished with a marble cupola and pillars; the upper part of the church was rebuilt, and a monastery was built alongside it, with accommodation for pilgrims and a hospital. A few decades later, after Jerusalem was re-taken by Saladdin, the church was again destroyed, and all that was left was the crypt, the front wall and the stairway between them, with its two chapels: that is what makes up the present church.

Body and soul

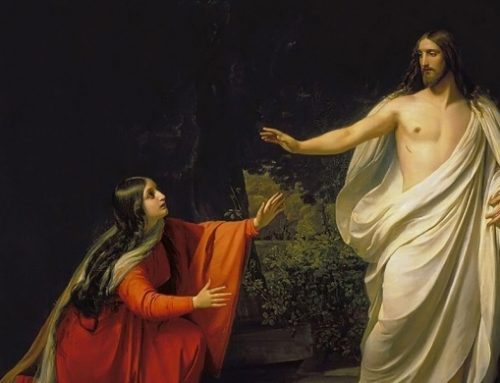

“The mystery of Mary’s Assumption body and soul is fully inscribed in the resurrection of Christ. The Mother’s humanity is ‘attracted’ by the Son in his own passage from death to life. Once and for all, Jesus entered into eternal life with all the humanity he had drawn from Mary; and she, the Mother, who followed him faithfully throughout her life, followed him with her heart, and entered with him into eternal life which we also call heaven, paradise, the Father’s house” (Pope Francis, homily, 15 August 2013). At the same time, “the Assumption is a reality that touches us too, for it points us in a luminous way toward our destiny, that of humanity and of history. In Mary, indeed, we contemplate that reality of glory to which each one of us and the entire Church is called” (Benedict XVI, Angelus, 15 August 2012).

“Our Lady, a full participant in the work of our salvation, follows in the footsteps of her Son: the poverty of Bethlehem, the everyday work of a hidden life in Nazareth, the manifestation of his divinity in Cana of Galilee, the tortures of his passion, the divine sacrifice on the Cross, the eternal blessedness of paradise.

All of this affects us directly, because this supernatural itinerary is the way we are to follow. Mary shows us that we can walk this path with confidence. She has preceded us on the way of imitating Christ, and her glorification is the firm hope of our own salvation. For these reasons we call her ‘our hope, cause of our joy’.

J. Gil in josemariaescriva.info

Leave A Comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.