Domingo Ramos-Lisson about the shows of the ancient Rome

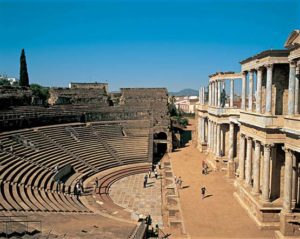

The grandest feasts, together with the distribution of food and alimentation, were the best means for the emperors to win the public. In almost all the important cities of the west, the concept of the “amphitheatre,” the “circus” had been introduced as magnificent centers of entertainment. To cite a few, the eloquent testimonies of such spectacles in Tréveris, Nimes, Sagunto, Mérida, Italica, Cartagena and Rome have become known to us.

To be able to have an idea of how it was during these ancient times, we can recall some few examples. The feasts and forms of public entertainment celebrated by the emperor Tito when he inaugurated the Colosseum lasted for 100 days. Trajan celebrated the year 106 with a series of festivals that lasted 123 days.

The capacity of the venues for these spectacles surpasses that of our modern stadiums. The Colloseum of Rome contained seats for 80,000 persons. The grand amphitheatre of the same city had a capacity for 250,000 spectators.

What kind of shows existed during the time of the Roman Empire?

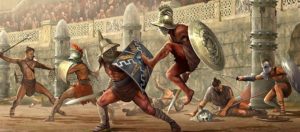

We can say that there were three main types: the races, the gladiator combats with the wild beasts, and the theatre. The races had, by its very nature, a particular moral dilemma: in some cases, judging from the way they were done, they showed cruelty and disdain for human life. The latter is emphasized in the case of the gladiator combats, and in the theatre which carried with it a certain sense of immorality.

Can you tell us something about the “combats” in the amphitheatre?

Of course, I haven’t talked about them in detail, but they are also relevant, above all, in that of what we call “grandest forms of entertainment”. Let’s consider some facts. In the eight games that Augustus held during his reign, 100,000 men fought.

On the other hand during the reign of Trajan, another 100,000 men fought. In certain occasions, it reached a point when real scenes of naval battles were re-enacted, also called naumachias. This was what Augustus organized during the inauguration of the temple of Mars Ultor for which he ordered the contruction of a basin complex that contained a lake, where 30 war ships of a total of 6,000 soldiers fought with each other.

It is important to point out that these combats were not staged or rehearsed, but were rather real, with the purpose of enlivening the low spirits of the spectators: a form of macabre “amusement” we might add.

In what sense can the cruelty demostrated in the gladiator combats be described?

We can start by saying that a significant number of the criminals and prisoners of war were chosen for these bloody combats. Certain organizations were in fact formed to assign people to these gladiator battles. One of the famous gladiator-slaves who managed to lead an uprising against the Roman Republic was Spartacus in 74 AD.

These battles usually commence with a ceremonial march across the arena. The battle proper abruptly starts either one on one or by groups. The gladiator battles had a certain level of morbidity as human blood was freely spilled across the battleground. If one of the gladiators found himself gravely hurt, his life depended on the judgment of the public present in the arena. A raised thumb meant clemency while the opposite meant death.

The important German historian Mommsen, author of A History of Rome, wrote an account of these gladiator battles, saying that they were “a manifestation, and at the same time, a continuous act of promoting the demoralization of the ancient world… a spectacle of cannibals…, the darkest form of amusement that Rome ever had”.

Can we say that the battles with wild beast were less cruel form?

At first, it would be easy to imagine “battles of wild beasts” or venationes as a kinder or less brutal form of battle. However, in reality, it was even worse. It consisted in introducing wild beasts in battles against men: may it be gladiators, those condemned to death, or later, the Christians. The spectacle was fierce and horrible.

The Roman public was very demanding and was not satisfied with just any wild animal. They chose lions and tigers especifically those from Africa. For two or three weeks before the battle, the animals were starved in order to increase their appetite and voracity in time for the battle.

Some figures can illustrate better this context. In the games of Emperor Severus (222-235), which were held for seven days, 700 wild beasts were sacrificed while the number of men who died in these battles has not been tallied. Nero launched one time a division of Praetorians against 400 bears and 300 lions, which turned out to be one of the most barbaric battles ever held in Rome.

In terms of executions, in this case of death sentences, the spectacle again took on a cannibalistic and bloody nature. In this manner, a good number of harmless Christians were sacrificed before the fury of the masses.

What can be said about the mime and other theatrical presentations?

In principle, it can be said that theatre in the Roman Empire offered less exciting entertainment compared to that of the infamous races and gladiator battles. Rome maintained three theatres, within more than 10,000 localities. The theatrical presentations reflected the moral degeneration that was characteristic of the times, propelled mainly by paganism.

The “mimes” were performances of actors that without the use of words expressed in the form of dance and movement the songs that the choir sang along with musical accompaniment. The themes portrayed were often lifted from mythology, added with some sensual or erotic content.

The old classical dramas were staged only in a few occasions. The more commonly staged type of play were the comedies. Given the known corruption of the public who frequented the theatre during those times, scandalous scenes of adultery were usually included in these comedies. In fact, during the time when Christianity was more extensive in the third and fourth centuries, these plays ridiculed certain aspects of the sacramental life of Christians like baptism.

Given this scenario in ancient Rome, what was the reaction of the christians to all these?

Obviously, the reaction couldn’t have been any other than rejection: in most of the cases, due to the intrinsic incompatibility of Christian doctrine and the cruelty present in the different “spectacles”. It can also be said that the simple act of being there present in the “spectacles” made the public an accomplice to the grave, immoral nature of the shows. In other occasions, the Christians themselves were the sacrificed protagonists upon the swing of the sword or the attack of the wild beasts.

The theatre was also something similar given that its immorality was clearly evident and went against the life and faith of the Christians. Moreover, it can also be warranted that the different theatrical shows ridiculed and satirized gravely Christianity. Like what we have just pointed out, the mere attendance in these shows was understood as participation in the diversion and enjoyment of such “spectacles”. From these shows did the ecclesiastical authorities strongly discouraged participating in such theatre.

Can you recommend us some cathechetical during the third century that might illustrate more clearly the prohibition of participating in such forms of entertaiment with respect to the act of receiving the sacrament of baptism among early christians?

I can cite for example the “Apostolic Tradition” of Hippolytus of Rome. In this catechetical and liturgical work, it’s indicated that before receiving catechumenical instruction, the prospective catechumen would be asked a number of questions about his or her interest or participation in any such type of “profession”. The practice of some related profession may be seen as a grave impediment in receiving baptism, unless the candidate decides to quit from it.

Among the prospective candidates who found themselves in such situations were the chauffers of the chariots of horses used in the games, the gladiators and their trainers, and those who managed the wild beasts in the arena. The same treatment was given to the actors involved in the theatrical shows.

Tertullian, who wrote in the second and third centuries, was very solid in denouncing these shows because they promoted idolatry. In this sense, he writes:

“Everything in the paganistic spectacles is idolatry: its origins that remind of some gods; its names, taken equally from those gods… in the theatre, the kingdom of Venus and Liber; in the games, the memory of eponymous gods; in the gladiator combats, the ancient sacrifices of such gladiators that supposed a certain transformation; the amphitheatre, consecrated with more ceremonies than the Capitollium –a pandemonium where Mars and Diana occupy the highest places… the pagans didn’t claim to have been mistaken: the key sign by which the new Christain was known was that he doesn’t participate anymore in these spectacles; if he goes back, then he´s a traitor”. (On idolatry, XII-XXIV).

In summary, we can add other testimonies of Christians from that era; but what we have pointed out seems more than sufficient to illustrate the contrast between the ludicrous nature of pagan Rome and the life of the early Christians. Our early brothers in the faith not only suffered with their own flesh the violence and the cruelty of these spectacles, but also, the ridicule and mockery of the theatrical shows, which used Christianity as an object of the public’s diversion.

Leave A Comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.