“Forgiveness is asked for, is asked of another, and in Confession we ask for forgiveness from Jesus. Forgiveness is not the fruit of our own efforts but rather a gift, it is a gift of the Holy Spirit who fills us with the wellspring of mercy and of grace that flows unceasingly from the open heart of the Crucified and Risen Christ.” Pope Francis, Audience, 19.2.2014

1. Why go to Confession?

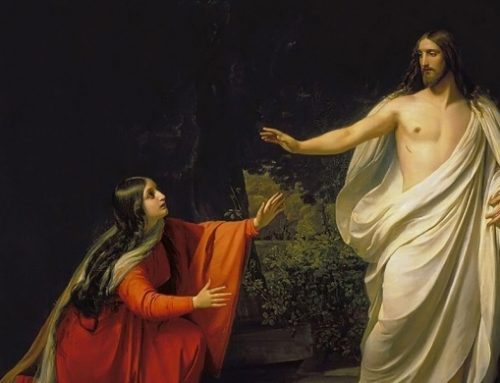

Confession, or Reconciliation, is a sacrament that Jesus Christ instituted to forgive sins, when he said to his Apostles: “If you forgive the sins of any, they are forgiven; if you retain the sins of any, they are retained” (Jn 20:23).

Because the new life that was given to us by him in Baptism may be weakened and lost by our sin, Christ chose that his Church should continue his work of curing and salvation through the Sacrament of Reconciliation.

Through the sacramental absolution given by the priest in Christ’s name, God grants the penitent forgiveness and peace. The penitent recovers the grace of living as a child of God, and can reach Heaven and eternal happiness.

Cf. Catechism of the Catholic Church, 1420-1421; 1426; 1446.

2. What is sin?

Sin is (…) failure in genuine love for God and neighbour caused by a perverse attachment to certain goods. It wounds the nature of man and injures human solidarity.

St Augustine calls it “love of oneself even to contempt of God.” In this proud self-exaltation, sin is diametrically opposed to the obedience of Jesus, which achieves our salvation (cf. Phil 2:6-9).

Sins are evaluated according to their gravity; the Church distinguishes between mortal and venial sin. Mortal sin destroys charity in the heart of man by a grave violation of God’s law; it turns man away from God, who is his ultimate end and his beatitude, by preferring an inferior good to him. Venial sin allows charity to subsist, even though it offends and wounds it.

For a sin to be mortal, three conditions must be met. Mortal sin is sin whose object is grave matter and which is also committed with full knowledge (full awareness) and deliberate consent.

Grave matter is specified by the Ten Commandments, corresponding to the answer of Jesus to the rich young man: “Do not kill, Do not commit adultery, Do not steal, Do not bear false witness, Do not defraud, Honor your father and your mother” (Mk 10:19). The gravity of sins is more or less great: murder is graver than theft. One must also take into account who is wronged: violence against parents is in itself graver than violence against a stranger.

One commits venial sin when, in a less serious matter, he does not observe the standard prescribed by the moral law, or when he disobeys the moral law in a grave matter, but without full knowledge or without complete consent.

Venial sin weakens charity; it manifests a disordered affection for created goods; it impedes the soul’s progress in the exercise of the virtues and the practice of the moral good; it merits temporal punishment. Deliberate and unrepented venial sin disposes us little by little to commit mortal sin.

Cf. Catechism of the Catholic Church, 1849–1864.

3. What is necessary for a good Confession?

The following are necessary for a good Confession: a diligent examination of conscience on sins committed since our last Confession; contrition, or repentance; confession, or the accusation of our sins before a priest; and the satisfaction, or penance, given by the confessor to the penitent to atone for the harm caused by our sins.

To examine our conscience, it helps to review the sins we have committed since our last confession in the light of the ten commandments, the Sermon on the Mount, and the teachings of the Apostles.

Contrition consists of sorrow of the soul and detestation for the sin committed, because it offends God and other people; together with the resolution not to sin again.

Through the confession (or disclosure) of sins, man looks squarely at the sins he is guilty of, takes responsibility for them, and thereby opens himself again to God and to the communion of the Church. All mortal sins of which penitents after a diligent self-examination are conscious must be recounted by them in confession, even if they are most secret (…); for these sins sometimes wound the soul more grievously and are more dangerous than those which are committed openly.

Confession of all the sins we have committed shows true contrition and our desire for God’s mercy. It is like a sick person showing his wound to the doctor so he can be healed.

Satsifaction or penance. Many sins wrong our neighbour. We must do what is possible in order to repair the harm (e.g., return stolen goods, restore the reputation of someone slandered, pay compensation for injuries). Simple justice requires as much. But sin also injures and weakens the sinner himself, as well as his relationships with God and neighbour. Absolution takes away sin, but it does not remedy all the disorders sin has caused. Raised up from sin, the sinner must still recover his full spiritual health by doing something more to make amends for the sin: he must “make satisfaction for” or “expiate” his sins as instructed by the confessor.

Cf. Catechism of the Catholic Church, 1451, 1455, 1456, 1459.

4. Why ask for forgiveness from a man, and not God directly?

Only God forgives sins (Mk 2:7). Since he is the Son of God, Jesus says of himself, “The Son of man has authority on earth to forgive sins” (Mk 2:10), and exercises this divine power: “Your sins are forgiven” (Mk 2:5; Lk 7:48).

Further, by virtue of his divine authority he confers this power on the Apostles (cf. Jn 20:21-23) and their successors to exercise in his name. Christ has willed that his Church should be the sign and instrument of the forgiveness and reconciliation that he acquired for us at the price of his blood. But he entrusted the exercise of the power of absolution to the apostolic ministry. Therefore the priest hearing Confessions acts “in the name of Christ” and “it is God himself” who, through the priest, tells us: “Be reconciled with God” (cf. 2 Cor 5:20).

Cf. Catechism of the Catholic Church, 1441, 1442.

5. How often should we go to Confession?

After having attained the age of discretion, each of the faithful is bound by an obligation faithfully to confess serious sins at least once a year. Anyone who is aware of having committed a mortal sin must not receive Holy Communion, even if he experiences deep contrition, without having first received sacramental absolution. The Church strongly recommends the habitual confession of venial sins, as this helps the faithful form their conscience, fight against evil inclinations, welcome Christ’s healing, and make progress in the life of the Spirit. Children must go to the sacrament of Penance before receiving Holy Communion for the first time.

Christ’s call to conversion continues to resound in the lives of Christians. This (…) is an uninterrupted task for the whole Church who, “clasping sinners to her bosom, [is] at once holy and always in need of purification, [and] follows constantly the path of penance and renewal” (Lumen Gentium, 8). This endeavor of conversion is not just a human work. It is the movement of a “contrite heart,” drawn and moved by grace to respond to the merciful love of God who loved us first (cf. Ps 51:19; Jn 6:44; Jn 12:32; and 1 Jn 4:10).

The process of conversion and repentance was described by Jesus in the parable of the prodigal son, the centre of which is the merciful father (Lk 15:11-24). The fascination of illusory freedom, the abandonment of the father’s house; the extreme misery in which the son finds himself after squandering his fortune; his deep humiliation at finding himself obliged to feed swine, and still worse, at wanting to feed on the husks the pigs ate; his reflection on all he has lost; his repentance and decision to declare himself guilty before his father; the journey back; the father’s generous welcome; the father’s joy – all these are characteristic of the process of conversion. The beautiful robe, the ring, and the festive banquet are symbols of that new life – pure worthy, and joyful – of anyone who returns to God and to the bosom of his family, which is the Church. Only the heart of Christ who knows the depths of his Father’s love could reveal to us the abyss of his mercy in so simple and beautiful a way.

Cf. Catechism of the Catholic Church, 1428, 1439, 1457.

Leave A Comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.