The origins of Christmas

THE PRACTICE OF THE LITURGICAL CELEBRATION OF CHRISTMAS BECAME WIDESPREAD. IN THE SECOND HALF OF THE FOURTH CENTURY, IT IS CELEBRATED BY MOST CHRISTIANS: THOSE IN NORTH AFRICA (360 AD), IN CONSTANTINOPLE (380 AD), IN SPAIN (384 AD) AND IN ANTIOCH (386 AD). IN THE FIFTH CENTURY, CHRISTMAS BECAME A UNIVERSAL CELEBRATION.

Texts about the origins of how Christmas was celebrated

The first generation Christians, that is to say, those who directly listened to the preaching of the Apostles, knew well and meditated on the life of Jesus frequently, especially on his most important moments: his passion, redemptive death and glorious resurrection.

They also knew well his miracles, his parables and the many details of his preaching. It was what they had heard that made them follow the Lord during his public life, to which they had been direct witnesses.

As for Jesus’s childhood, they only knew some details that perhaps Jesus himself or his Mother narrated; while most of them were kept by Mary in her heart.

In the gospels, written are most significant details about the birth of Jesus. From different perspectives, Matthew and Luke record essential facts such as that Jesus was born in Bethlehem in Judea, of the Virgin Mary, whose spouse was Joseph, but without her having known any man. In addition, towards the end of the accounts on the childhood of Jesus, both indicate that they later went to live in Nazareth.

Matthew emphasizes that Jesus is the Messiah, descendant of David, the Savior through which the promises of God to the old tribe of Israel have been fulfilled. For that reason, as the promise of Jesus to the tribe of David comes fulfilled by being the legal son of Joseph, Matthew narrates the facts especially paying attention to the assignment of the Holy Patriarch.

On the other hand, Luke centers on the Virgin —who also represents the faithful humanity to God— as a sign that the Boy that is born in Bethlehem is thepromised Savior, the Messiah and Lord, who has come to the world to save all men.

In the second century, the desire to know more about the birth and childhood of Jesus caused some pious people, without precise historical information, to invent fantastic stories from their imagination. Some of these stories are recorded in apocryphal gospels. One of the more developed stories on the birth of Jesus contained in the apocryphals is the one that appears in what is called The Protogospel of St. James, according to other manuscripts, – about the Birth of Mary, written in the middle of the second century.

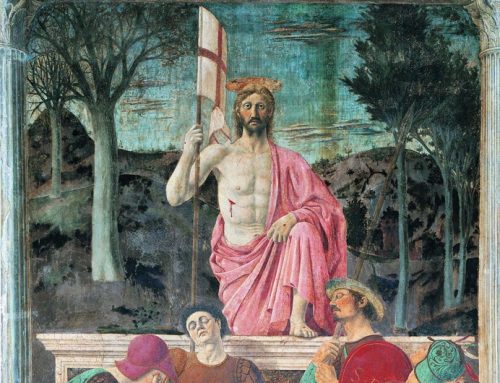

For the first generations of Christians, the most important feast was the Passover, a commemoration of the Resurrection of the Lord. All knew well on which dates Jesus was crucified and when he resurrected: on the central days of the celebration of the Jewish feast of Passover, around the 15th day of Nisan, that is to say, the day of Full Moon of the first month of spring.

However, they possibly did not know with the same certainty the time of his birth. The celebration of the birth of Jesus then was not part of the customs of the first Christians.

Christ was born in Bethlehem in Judea on the 25th of December

The third century, there had been no information on the exact day of the birth of Jesus. The first testimonies of ecclesiastical writers and Church Fathers specify different dates. The first indirect testimony of which the birth of Christ was dated to the 25th of December was during theSixth African July in 221 AD.

The first direct reference to its celebration is the one of the liturgical Philocalian calendar dating from 354 AD (MGH, IX, i, 13-196): VIII kal. Ian. natus Christus in Betleem Iudeae (“the Christ was born in Bethlehem in Judea on the 25th of December”).

As of the fourth century, the testimonies referring to this day as the date of the birth of Christ have become common in western tradition, whereas in the East, the 6th of January prevails as the date of birth of Jesus.

An explanation for why the Christians chose that day, as of 274 AD, was that on the 25th of December, the dies natalis Solis invicti (the days of the birth of the Unconquered Sun), the victory of the light on the longest night of the year, is celebrated in Rome.

This explanation leans towards the parallelism established between the birth of Jesus Christ and Biblical expressions like “sun of justice” (Mt 4.2) and “light of the world” (Jn 1,4ss.), maintained by Church Fathers of that time. However, there are no proofs for this and is quite difficult to explain especially that the Christians of that time then wanted to adopt pagan celebrations in the liturgical calendar, especially after the persecution.

A more plausible explanation sets the date of the birth of Jesus dependent on the date of his incarnation which was related as well to the date of his death. An anonymous reference about solstices and equinoxes affirms that “our Lord was conceived on the 8th of the calendar of April in the month of March (25th of March), that is the day of the passion of the Lord and his conception, because he was conceived on the same day he died” (B. Botte,Them Origenes of Noel et of l’Epiphanie, Louvain 1932, l. 230-33).

In the Eastern tradition, pertaining to another calendar, the passion and the incarnation of the Lord is celebrated on the 6th of April, a date that agrees with the celebration of Christmas on the 6th of January.

The relation between the passion and the incarnation is an idea which is consistent with old, medieval thinking, which admired the perfection of the universe as a whole, where the great interventions of God were unified. Another one is a concept that also finds its roots in Judaism, in which creation and salvation were related to the month of Nisan.

Christian art has reflected this same idea throughout history, evident from the painting of the Annunciation to the Virgin with the Child Jesus descending from the sky with a Cross. Therefore, it is possible that the Christians connected Christ’s redemption to his conception, and it determined the date of his birth. “The most decisive part was the existing relation between creation and the cross, between creation and the conception of Christ” (J. Ratzinger, the spirit of the liturgy, 131).

The practice of the liturgical celebration of Christmas became widespread. In the second half of the fourth century, it is celebrated by most Christians: those in North Africa (360 AD), in Constantinople (380 AD), in Spain (384 AD) and in Antioch (386 AD). In the fifth century, Christmas became a universal celebration.

FRANCISCO VARO

PROFESSOR OF SACRED SCRIPTURE

FACULTY OF THEOLOGY

UNIVERSITY OF NAVARRA

Leave A Comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.